The newsreel over the last week has been like a movie, with several plotlines running concurrently: coronavirus, OPEC, the 2020 election, and continued trade tensions. Over the past several weeks, these separate plotlines, with their respective twists and turns, have evoked pessimism and concern among the public, which has led to selloffs in global stock and bond markets. Here, we will aim to address the three major plotlines we see as currently posing the greatest risk of further destabilizing the markets.

Plot #1: Coronavirus/COVID-19

On December 31st, 2019, Chinese health authorities indicated that a type of mysterious illness was cropping up in Wuhan. Two months later, what is now called COVID-19 (or simply the “coronavirus”) has spread around the globe, infecting over 116,000 individuals and killing close to 4,100. While governments have been mobilizing their countries’ respective healthcare industries to prevent and treat cases within their borders, economists and investors alike have been speculating on the coronavirus’s long-term effects on the world economy.

As mentioned in our previous commentary, little reliable data is available. China’s information flow has long been regulated by its government, and thus may be of poor integrity. Data from the rest of the world is limited due to the delay between data gathering and data reporting. In other words, entities that collect and release information are most likely just beginning to compile data from February, which will most likely not be released for several weeks. All this has increased uncertainty, as the impact of coronavirus is currently unmeasurable. Markets seem to be anticipating an economic calamity, with the S&P 500 plummeting 19% since its February peak (just before the surge of cases appeared in Western Europe and the Middle East).

Our formal stance is that the coronavirus could cause a global economic disturbance, but hard evidence is necessary to determine for how long or to what degree of severity. To date, most “evidence” has been largely based on speculation. For us to be concerned about a sustained global economic slowdown, we would need to see breakdowns in global supply chains. This would be indicated by collapsing new order flows, hiring freezes, and unsold inventory buildups. We receive this data from the Institute for Supply Management, American Chemistry Council, and IHS Markit each month. The figures for the month of February indicated little economic impact outside of China from the virus thus far. Data for March begins to be released at the end of this month.

Plot #2: Governmental Flailing

As would be expected, the populace has looked to the government for guidance and protection. Speaking strictly from an economic point of view, the Federal Reserve has thus far been the only domestic government entity to attempt to provide significant relief, implementing an “emergency” 0.50% interest rate cut last Tuesday.

The attempt to calm the market backfired, as the public viewed the move as panicky. “The Federal Reserve was already scheduled to meet on March 18th. Why couldn’t they wait another two weeks to make the cut?” was a common thought. Previous emergency cuts appeared following major events such as the Russian default in 1998, the bursting of the dot-com bubble, 9/11, and the collapse of Lehman Brothers. Now, with the general public fearful, the hope is that rates will be cut significantly again during the Fed meeting next Wednesday.

A few blocks south and then down Pennsylvania Avenue, Congress and the President have not yet rolled out any sort of widespread stimulus. There has been talk of temporary payroll tax cuts and loan relief programs for airlines and air cargo companies, but at this point, no material measures have been undertaken to spur economic activity. The lack of a coordinated, bipartisan effort to counter any potential economic weakness caused by coronavirus has been viewed in a negative light by investors.

Plot #3: OPEC Breakdown/Oil Glut

Oil fell to $30 per barrel on Monday, which in percentage terms marked the largest daily drop in the price of oil since the Gulf War. This was the result of a breakdown in talks between the member nations of OPEC on reducing oil production to increase prices. Russia, which is one of the member nations, explicitly disagreed and said it would be increasing production in an effort to drive US shale out of business. This development added fuel to the fire (pun intended), causing the market to decline further.

The relationship between oil and the economy is a volatile one. When the US imported most of its oil, declines in oil prices, and therefore gas prices, would stimulate the American economy with little exception. Now, with America having a booming oil production industry of its own and being a net exporter of petroleum products, large drops in oil prices place considerable strain on many of the domestic oil-producing companies, especially frackers.

Thus, this week’s oil decline has been bad for domestic oil/natural gas companies. Moreover, most of the shale boom has been financed with debt, as exploration/extraction companies had to borrow significant amounts of money to build their infrastructure. As many shale-producing companies are relatively young, their creditworthiness is lackluster and they are very sensitive to changing business conditions. Large drops in oil prices hurt margins and quickly increase a company’s risk of defaulting on debt. With this week’s drop in oil prices, bond prices are reflecting increasing default risk from many energy companies.

If the price of oil makes it unprofitable to extract shale oil and natural gas, the fear is that jobs may be cut, which is bad for the consumer. Similarly, the banks that gave these companies loans would incur large losses if not paid back. Currently, the banks with the largest exposure to these loans are Bank of Oklahoma, Frost Bank, Cadence Bancorp, and Comerica. As would be expected, their stocks fell sharply in recent days.

Putting the Plots Together – What We See & What We Are Doing

First, when we surveyed the landscape for opportunities in January, we noticed that debt from young energy companies and banks was looking less appealing. Owning a small amount of this debt worked very well in 2019 (our position gained 11%), but our analysis suggested this would not be the case in 2020. As such, we reduced our position in risky debt by 75% before the recent market drawdown. Similarly, we reduced exposure to energy stocks in many accounts, opting for more stable sectors such as utilities and consumer staples.

As far as what is next for the market, the current market condition is deeply oversold. Additionally, the research from my award-winning white paper “Making the Most of Panic,” (you can download a copy by clicking here) indicates that the probability of a potentially large relief rally is increasing. We are waiting for the point where investors look at the market and say, “I know there is a lot of bad news out there, but stocks are such bargains right now!” and begin bidding up prices again. Beyond a relief rally from oversold conditions, though, we will rely on our economic indicators to tell us whether low oil prices and the coronavirus are materially disrupting the global economy, and take more defensive investment positions if and when those are deemed appropriate.

-Christopher Diodato, CFA, CMT

Stories Within Stories – Examining Recent Market Volatility

Plot #1: Coronavirus/COVID-19

On December 31st, 2019, Chinese health authorities indicated that a type of mysterious illness was cropping up in Wuhan. Two months later, what is now called COVID-19 (or simply the “coronavirus”) has spread around the globe, infecting over 116,000 individuals and killing close to 4,100. While governments have been mobilizing their countries’ respective healthcare industries to prevent and treat cases within their borders, economists and investors alike have been speculating on the coronavirus’s long-term effects on the world economy.

As mentioned in our previous commentary, little reliable data is available. China’s information flow has long been regulated by its government, and thus may be of poor integrity. Data from the rest of the world is limited due to the delay between data gathering and data reporting. In other words, entities that collect and release information are most likely just beginning to compile data from February, which will most likely not be released for several weeks. All this has increased uncertainty, as the impact of coronavirus is currently unmeasurable. Markets seem to be anticipating an economic calamity, with the S&P 500 plummeting 19% since its February peak (just before the surge of cases appeared in Western Europe and the Middle East).

Our formal stance is that the coronavirus could cause a global economic disturbance, but hard evidence is necessary to determine for how long or to what degree of severity. To date, most “evidence” has been largely based on speculation. For us to be concerned about a sustained global economic slowdown, we would need to see breakdowns in global supply chains. This would be indicated by collapsing new order flows, hiring freezes, and unsold inventory buildups. We receive this data from the Institute for Supply Management, American Chemistry Council, and IHS Markit each month. The figures for the month of February indicated little economic impact outside of China from the virus thus far. Data for March begins to be released at the end of this month.

Plot #2: Governmental Flailing

As would be expected, the populace has looked to the government for guidance and protection. Speaking strictly from an economic point of view, the Federal Reserve has thus far been the only domestic government entity to attempt to provide significant relief, implementing an “emergency” 0.50% interest rate cut last Tuesday.

The attempt to calm the market backfired, as the public viewed the move as panicky. “The Federal Reserve was already scheduled to meet on March 18th. Why couldn’t they wait another two weeks to make the cut?” was a common thought. Previous emergency cuts appeared following major events such as the Russian default in 1998, the bursting of the dot-com bubble, 9/11, and the collapse of Lehman Brothers. Now, with the general public fearful, the hope is that rates will be cut significantly again during the Fed meeting next Wednesday.

A few blocks south and then down Pennsylvania Avenue, Congress and the President have not yet rolled out any sort of widespread stimulus. There has been talk of temporary payroll tax cuts and loan relief programs for airlines and air cargo companies, but at this point, no material measures have been undertaken to spur economic activity. The lack of a coordinated, bipartisan effort to counter any potential economic weakness caused by coronavirus has been viewed in a negative light by investors.

Plot #3: OPEC Breakdown/Oil Glut

Oil fell to $30 per barrel on Monday, which in percentage terms marked the largest daily drop in the price of oil since the Gulf War. This was the result of a breakdown in talks between the member nations of OPEC on reducing oil production to increase prices. Russia, which is one of the member nations, explicitly disagreed and said it would be increasing production in an effort to drive US shale out of business. This development added fuel to the fire (pun intended), causing the market to decline further.

The relationship between oil and the economy is a volatile one. When the US imported most of its oil, declines in oil prices, and therefore gas prices, would stimulate the American economy with little exception. Now, with America having a booming oil production industry of its own and being a net exporter of petroleum products, large drops in oil prices place considerable strain on many of the domestic oil-producing companies, especially frackers.

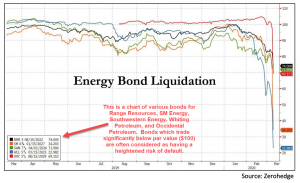

Thus, this week’s oil decline has been bad for domestic oil/natural gas companies. Moreover, most of the shale boom has been financed with debt, as exploration/extraction companies had to borrow significant amounts of money to build their infrastructure. As many shale-producing companies are relatively young, their creditworthiness is lackluster and they are very sensitive to changing business conditions. Large drops in oil prices hurt margins and quickly increase a company’s risk of defaulting on debt. With this week’s drop in oil prices, bond prices are reflecting increasing default risk from many energy companies.

If the price of oil makes it unprofitable to extract shale oil and natural gas, the fear is that jobs may be cut, which is bad for the consumer. Similarly, the banks that gave these companies loans would incur large losses if not paid back. Currently, the banks with the largest exposure to these loans are Bank of Oklahoma, Frost Bank, Cadence Bancorp, and Comerica. As would be expected, their stocks fell sharply in recent days.

Putting the Plots Together – What We See & What We Are Doing

First, when we surveyed the landscape for opportunities in January, we noticed that debt from young energy companies and banks was looking less appealing. Owning a small amount of this debt worked very well in 2019 (our position gained 11%), but our analysis suggested this would not be the case in 2020. As such, we reduced our position in risky debt by 75% before the recent market drawdown. Similarly, we reduced exposure to energy stocks in many accounts, opting for more stable sectors such as utilities and consumer staples.

As far as what is next for the market, the current market condition is deeply oversold. Additionally, the research from my award-winning white paper “Making the Most of Panic,” (you can download a copy by clicking here) indicates that the probability of a potentially large relief rally is increasing. We are waiting for the point where investors look at the market and say, “I know there is a lot of bad news out there, but stocks are such bargains right now!” and begin bidding up prices again. Beyond a relief rally from oversold conditions, though, we will rely on our economic indicators to tell us whether low oil prices and the coronavirus are materially disrupting the global economy, and take more defensive investment positions if and when those are deemed appropriate.

-Christopher Diodato, CFA, CMT

Join Our Mailing List